Before we get started, let’s get the uncomfortable part out of the way. We are a Wristband company, and we hope you’ll buy wristbands from us. But, we’re not going to try to work a sales pitch into this post, or the others in this series. This disclaimer is the only mention of wristbands you’ll see in each of these posts.

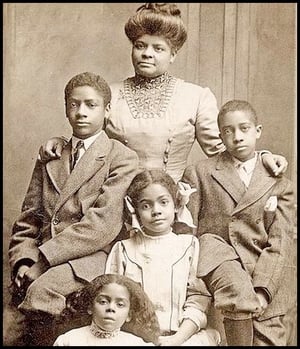

IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT (1862-1931)

For our second post in our Black History Month series (click here to read part one), we want to celebrate the life and legacy of one of our favorite trouble-making women in American history… Ida B. Wells.

Ida was one of the most important civil rights advocates of the 19th century. She was born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi, just before the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, freeing her and her parents. At the age of 16, she became the primary caregiver to her six brothers and sisters, when both of her parents died of yellow fever. After completing her studies at Rust College near Holly Springs, where her father had sat on the board of trustees before his death, Wells divided her time between caring for her siblings and teaching school. Once her brother’s had landed jobs and apprenticeships, Ida and her sisters moved to nearby Memphis to live with her aunt. Her life in Memphis paved the way for the activist she would become.

A TEACHER IN TENNESSEE

While living in Memphis, where she would eventually become a public school teacher, an important event happened that would shape the rest of her life. She needed to travel to a Memphis suburb, so she purchased a train ticket for the first-class ladies’ car. Eighty years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus, Wells refused the conductor’s order to move to another car. She had to be forcibly removed by the authorities.

Backed by the Civil Rights Act of 1875, Wells filed a lawsuit against the railroad. Surprising nearly everyone, including herself, she won the lawsuit, although the Tennessee Supreme Court soon overturned the victory. Frustrated by this outcome, she began writing political columns and articles in church newsletters and local newspapers. Using the money she had saved from her teaching job, she became part owner of a small newspaper called Free Speech and Headlight, which quickly became the most radical and talked about newspaper in Memphis.

A few years later, in 1891, Wells was fired from the Memphis school system for a strong article she wrote that exposed the unequal funding of black schools by the board of education. For the rest of her life, however, she would use the voice she discovered during this time to fight for civil and women’s rights and to fight against educational inequalities, lynching, and segregation.

THE SO-CALLED “CURVE RIOT”

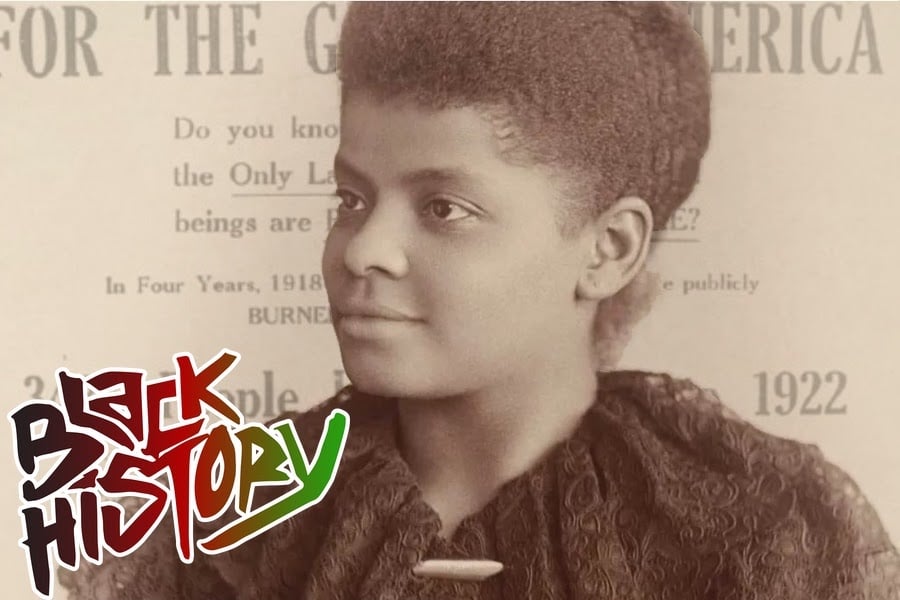

In 1892, three of Wells’ friends were lynched by a violent mob. Three black men - Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart - opened a grocery store, which drew customers away from a white-owned store in the neighborhood. This led to numerous clashes as the white owner and his supporters sought to put the new store out of business.

One night, Moss and the others guarded their store against the attack and ended up shooting several of the white vandals. They were arrested and brought to jail, but they didn't have a chance to defend themselves against the charges. A lynch mob took them from their cells and murdered them. This event became known as “The Curve Riot,” in an attempt to justify the lynchings, but it was a lie. There was no riot.

Wells began writing newspaper articles about the injustice of lynching, and exposed how it was not about punishing criminals, but about terrorizing and intimidating black people. Wells countered the “rape myth” used by lynch mobs to justify the murder of African Americans. Through her research, she found that lynching victims had challenged white authority or had successfully competed with whites in business or politics. While Wells was (fortunately) attending a conference in New York City, violence erupted again in Memphis. The offices of The Free Speech and Headlight were ransacked - all of the equipment was destroyed, and Wells’ co-owner was run out of Memphis. Wells was warned that she would be lynched herself if she returned to Memphis.

She stayed for a while in New York, joining the writing staff of The New York Age, and continuing her research and writing about lynching in America. This research, which proved that lynching was racially motivated terror meant to intimidate and silence black people and communities, was compiled into a small book called The Red Record, which is still available today.

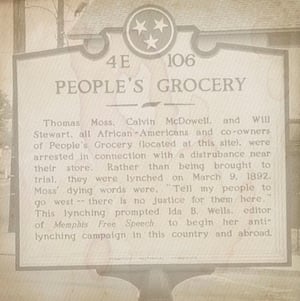

A CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER IN CHICAGO

Because of her writing and activism, Wells found herself unwelcome in the South. After a short stint in New York, and a lecture tour in England, during which she encouraged English manufacturers to boycott American cotton, she found her new home in Chicago. It was in Chicago that she met and married Ferdinand Barnett, an attorney and the editor of The Chicago Conservator, the city’s first African-American newspaper. She kept her last name, becoming Ida Wells-Barnett, an extremely radical and bold thing to do at the time. The couple had 4 children together.

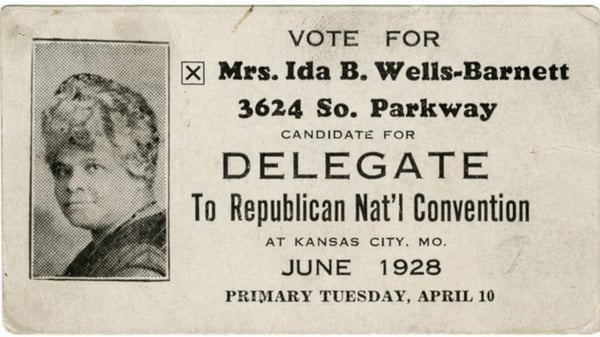

Despite staying home to raise her children, she worked to solve many of the issues facing black people, especially black women. She blocked the segregation of the school system. She established the first black kindergarten in her community. She helped form the National Association of Colored Women. She, along with W.E.B. DuBois (and others) founded the NAACP. She fought tirelessly for Women’s Suffrage and countless other political causes.

When she was sixty-eight, Wells ran for the Illinois legislature, one of the first black women in the nation to run for public office. A year later, in 1931, she died at the age of sixty-nine.

THE IDA B. WELLS LEGACY

She didn’t suffer fools and she saw fools everywhere.

~ Troy Duster, Wells’ grandson [1]

Ida B. Wells spent her life fighting for justice and equality. She truly believed that exposing injustice would lead to change, insisting that “the way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” She pioneered many of the investigative journalism practices still used today and is still inspiring journalists to follow in her footsteps.

She did not allow herself to be marginalized or silenced. Even though she faced threats, lost property, and endured criticism, she felt what she had to say was important enough to say it. She refused to be silent. She refused to make herself small. She stood up. Spoke out. And she made a difference for all of us.

Sources:

[1] Ida B. Wells Obituary - The New York Times

Want an easy way to show support for the black community? Check out this curated list of Black owned business to support all year round! From our friends at Website Planet: https://www.websiteplanet.com/blog/support-black-owned-businesses/

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)