Before we get started, let’s get the uncomfortable part out of the way. We are a Wristband company, and we hope you’ll buy wristbands from us. But, we’re not going to try to work a sales pitch into this post, or the others in this series. This disclaimer is the only mention of wristbands you’ll see in each of these posts.

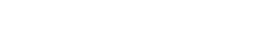

PAULI MURRAY (1910-1985)

For our fourth and final post in our Black History Month series (part one, part two, part three), we want to celebrate another unsung American hero… Pauli Murray, an American civil rights activist who became a lawyer, a women's rights activist, Episcopal priest, and author.

A REMARKABLE LIFE

Pauli Murray lived a truly remarkable life. A poet, writer, activist, labor organizer, legal theorist, and Episcopal priest, Murray was childhood friends with Langston Hughes, joined James Baldwin at the MacDowell Colony the first year it admitted African-Americans, was friends with Eleanor Roosevelt for over two decades, and helped Betty Friedan found the National Organization for Women.

Along the way, she formulated and articulated the intellectual and legal foundations of two of the most important social justice movements of the twentieth century: first, a paper she wrote while in college for overturning Plessy (“Separate but Equal”), and, later, when she co-wrote a law-review article that was subsequently used by a rising star at the A.C.L.U.—one Ruth Bader Ginsburg—to convince the Supreme Court that the Equal Protection Clause applies to women.

A FEW DECADES EARLY

It seems that for many aspects of Pauli’s life, she was a few decades ahead of her time. She not only pioneered the legal basis behind important cases in civil and women’s rights, she is also a queer icon that was open about her romantic involvement with other women, and struggled throughout her life with gender identity and gender expression.

Pauli Murray was a gender nonconforming person, who favored a more masculine-of-center gender expression. She struggled both with her sense of gender identity and with her sexual attraction to women. She asked doctors to administer male hormones to her in the 1930s, and tried to convince one doctor to perform exploratory surgery to see if she had “secreted male genitals.” In today’s terms, she very probably would have embraced a transgender identity, and might have identified as a trans man. That terminology, however, was not available to Murray in the 1930s and 1940s.

It is incredibly important to situate Murray within these trans and queer communities, because it helps explains why she isn’t remembered. The civil rights struggle demanded respectable performances of black manhood and womanhood, particularly from its heroes and heroines, and respectability meant being educated, heterosexual, married, and Christian. If society at large was going to treat blacks people as equal, they had to be seen as holding the same values as the dominant society. Murray’s open lesbian relationships and her gender nonconforming identity disrupted the dictates of respectability, making it easier to erase her five decades of important intellectual and political contributions from our broader narrative of civil rights, all to our great loss.

THE PASSIONATE POET PRIEST

The civil rights movement demanded Murray be educated, heterosexual, married, and Christian. Since she was two of those, (very well) educated and (passionately) Christian, she spent the final chapter of her life in church leadership. She was ordained in 1977, becoming the first black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. She performed her first Eucharistic service at the same church in which her grandmother, a slave, was baptized.

AN ENDURING LEGACY

Part of the work of Black History Month is to purposely bring to mind forgotten African-American contributions, and Pauli Murray’s accomplishments and firsts are so voluminous as to need multiple books to fully appreciate the magnitude of her contributions. But Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s courageous choice to name and highlight “the shoulders on which she stands” remind us that even though no African-American woman yet sits on the Supreme Court, the political legacy of black women’s contributions to America are present and powerful even when we cannot see them.

SOURCES:

The Many Lives of Pauli Murray

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)